Introduction

Inflation, once a statistical figure tucked away in economic reports, has now metastasized into a societal cancer, gnawing at the very core of our existence. This exposé plunges into the history of America's inflation crisis, which is centered around the rise and fall of the US dollar.

The Ominous Definition of Inflation

In understanding the ominous definition of inflation, it's crucial to grasp the historical context that shaped this economic metric. From ancient civilizations to modern economies, the specter of inflation has haunted societies dating back to the Roman Empire, often signaling the decline of economic stability and social equilibrium. The fundamental notion that more money in circulation leads to higher prices has been pivotal in shaping arguments advocating anti-inflation policies within central banking institutions today. However, it's crucial to acknowledge that over time, the understanding of inflation changed, transcending its narrow monetary origins to encompass a more comprehensive assessment of its ramifications: price increases. This evolution begs a haunting question: why did the definition morph from a singular focus on money supply augmentation to encompass the ominous specter of price escalations?

Historical Background

America's economic dominance has a history of changes since its founding. The constitutional mandate for using gold and silver as money stated in Article 10 of the constitution, enshrined by the founding fathers, reflects a historical aversion to currency devaluation and uncontrolled money supply growth that led to every great empire's failure due to inflation, like the Roman Empire. The founding fathers were outspoken against central banks and paper money (Fiat). Figures like Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Andrew Jackson, and James Madison ring eerily, warning of the perils posed by central banks, spiraling debts, and the insidious grip of inflationary pressures. The following are some important warnings they issued:

"If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation, then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around them will deprive the people of all property until their children wake up homeless on the continent their Fathers conquered.” - Thomas Jefferson

James Madison, an unsung yet prescient founding father, warned: “History records that the money changers have used every form of abuse, intrigue, deceit, and violent means possible to maintain their control over governments by controlling money and its issuance.”

Andrew Jackson, championing the American cause against central banking, declared: “If Congress has the right under the Constitution to issue paper money, it was given them to use themselves, not to be delegated to individuals or corporations.”

The Pre-Federal Reserve of Inflation Dynamics

Before the Federal Reserve's establishment in 1913, America experienced a period of price stability and modest inflation rates. The gold standard's discipline reined in rampant money supply expansion, maintaining a semblance of economic equilibrium. This era serves as a benchmark for understanding the seismic shifts in inflation dynamics post-Fed.

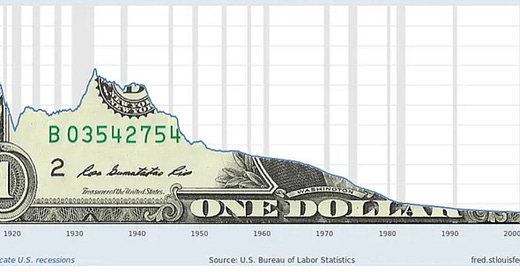

Before the advent of the Federal Reserve in 1913, America basked in the glow of relatively stable prices and meager average annual inflation rates. Federal Reserve archives reveal a modest annual inflation rate of a mere 0.4% during the pre-Fed era (1790-1913). This historical backdrop assumes paramount importance in gauging the tremors of inflation's impact and the undercurrents of economic stability across epochs (St. Louis Federal Reserve, 2017). The steadfast adherence to the gold standard provided a tether of discipline in monetary and fiscal policies by the government, restraining the rampant expansion of the money supply and the attendant inflationary onslaught.

The Transition to Fiat Currency

The establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913 heralded a seismic shift from the shackles of a gold-backed currency to the uncharted waters of a fiat currency regime. This transition ushered in an era of purported monetary flexibility but also birthed unprecedented challenges in navigating inflation, interest rate dynamics, and the precarious tightrope of financial stability. The intricate interplay between money supply surges, inflationary pressures, and the ebbs and flows of economic cycles birthed a labyrinth of complexities, causing numerous boom-and-bust cycles around speculative bubbles and inflationary nightmares.

The Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression and Post-WWII Reckonings

The aftermath of the Roaring Twenties, characterized by unfettered money expansion, saw the Federal Reserve ratcheting up interest rates to an unprecedented 6% by 1929.

This seemingly prudent move unveiled the harrowing reality of overvalued stocks, with higher rates exerting a suffocating downward pressure on economic vitality, culminating in the cataclysmic crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression of the 1930s.

This crucible of economic tribulations laid bare the limitations of conventional monetary dogmas and unraveled the perilous dance with deflationary spirals. The Federal Reserve's initial missteps in the interest rate trajectory compounded economic contractions and precipitated widespread bank insolvencies.

The ensuing policy acrobatics, including the abandonment of the gold standard under President FDR's Executive Order 6102, symbolized a desperate bid to jolt the economy from its stupor. The money supply witnessed a 42% surge in money supply between 1933 and 1941, accompanied by a 30% uptick in price levels. Revisionist historians have erroneously labeled this era as deflationary, concealing the underlying inflationary currents. Most history books today write about the 1930s as the Great Depression with prices continuing to drop. But what actually happened after 1933 was that the US dollar lost about 40% in purchasing power, meaning that prices were actually rising. This monetary storm sent massive distortions throughout the economy in the 1930s.

The Post-World War II Ushered in the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, pegging major currencies to the U.S. dollar tethered to gold at $35 per ounce, charting a course for international monetary cohesion amidst the echoes of war-torn upheavals. The reason why the world agreed upon the US dollar as the world reserve currency was:

The United States won the world war and was the only producing industrial might left compared to the rest of the world, so the rest of the world powers really didn't have much to offer since many of the countries' infrastructure and industrial capabilities were destroyed during World War II.

The US dollar being the world reserved currency was a no-brainer because it was backed by 1 ounce of gold per $35, meaning that for every dollar countries held, it was equivalent to an ounce of gold so the dollar was as good as gold.

(To complete your journey through the captivating narrative of the Rise and Fall of the US dollar, why not become a valued subscriber? By joining us, you not only gain access to the rest of this compelling story but also contribute to our mission of delivering the most comprehensive market news, insightful analysis, valuable data, and rich historical references. Your support empowers us to continue providing you with unparalleled content and expertise.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Coastal Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.