The G.O.A.T Stock Market Bubble vs. Newton's Law of Gravity

What wins, Irrational Exuberance or the Force of Gravity?

Prepare to embark on a thrilling odyssey into the heart of the financial world, as this comprehensive financial exposé unravels the enigma of the Greatest Of All Time (GOAT) stock market bubble. Echoing the tumultuous reverberations of historical economic upheavals, this analysis steps into the shadows of past financial crises, with a haunting reminder of the legendary South Sea Bubble that captivated Isaac Newton's era.

In today’s Stockmarket , the air crackles with anticipation, reminiscent of the charged atmosphere preceding historic market downturns. The analysis ignites with a blinding spotlight on key economic indicators, each pulsating with a sense of urgency akin to the Tech Bubble 1.0 in 2000. The numbers soar to dizzying heights, flashing bright red warnings that echo the precipices of previous market collapses.

But the drama intensifies as we plunge into the realm of market valuations, where the colossal figures of the "Magnificent Seven" tech titans cast looming shadows. Their exorbitant price-to-earnings ratios stand as stark contrasts against an inflated market backdrop. The heartbeat of the financial world quickens as the Shiller PE ratio blares a red-alert level of 34, surpassing even the ominous signs of 1929, 2000, and 2021. The Federal Reserve's decision to raise interest rates to 5.5%, reminiscent of past Stock Market peaks like in 1929, 1987, 2000, 2008, coupled with persistent inflation, adds fuel to the raging inferno of uncertainty.

Against this backdrop of flashing red indicators and economic tumult, a question looms large: can the GOAT Stockmarket bubble defy Newton's immutable law of gravity? Prepare to witness the clash of irrational exuberance against the gravitational pull of economic reality.

South Sea Bubble: Isaac Newton Experiences a taste of his own Law of Gravity

“I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the greed and exuberance of people.”

― Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton's entanglement in the South Sea Bubble serves as a stark reminder of the seductive allure and treacherous pitfalls of speculative markets, even for a mind as brilliant as his. Revered for his groundbreaking contributions to physics and mathematics, Newton's intellect was unmatched in his time and continues to inspire awe today.

However, amidst his genius, Newton was not impervious to the charms of market exuberance. The South Sea Bubble, a feverish financial craze that gripped early 18th-century England, promised unimaginable riches through the South Sea Company's exclusive trade rights with Spanish colonies.

Initially cautious, Newton eventually succumbed to the allure of quick profits. He purchased South Sea Company stock, enticed by the company's aggressive marketing and exaggerated promises of wealth. His decision was not purely driven by greed but also influenced by peer pressure and the prevailing mood of speculative mania.

As the bubble inflated to dizzying heights, Newton, like many others, saw his investments surge in value. Sensing an opportunity to capitalize on his gains, he made the decision to sell his shares, only to watch in dismay as prices continued to skyrocket.

In a twist of irony, Newton, renowned for his mastery of natural laws, including gravity, defied financial gravity by re-entering the market at its peak. His belief in the unsustainable rally led him to buy back into South Sea stock at inflated prices, a decision that would prove disastrous.

The subsequent collapse of the South Sea Bubble in 1720 shattered Newton's financial portfolio, resulting in substantial losses. His experience serves as a sobering reminder that even the brightest minds can be lured into reckless speculation during periods of market euphoria.

Law Of Gravity Victories Vs. Previous US Stockmarket Bubbles

1929

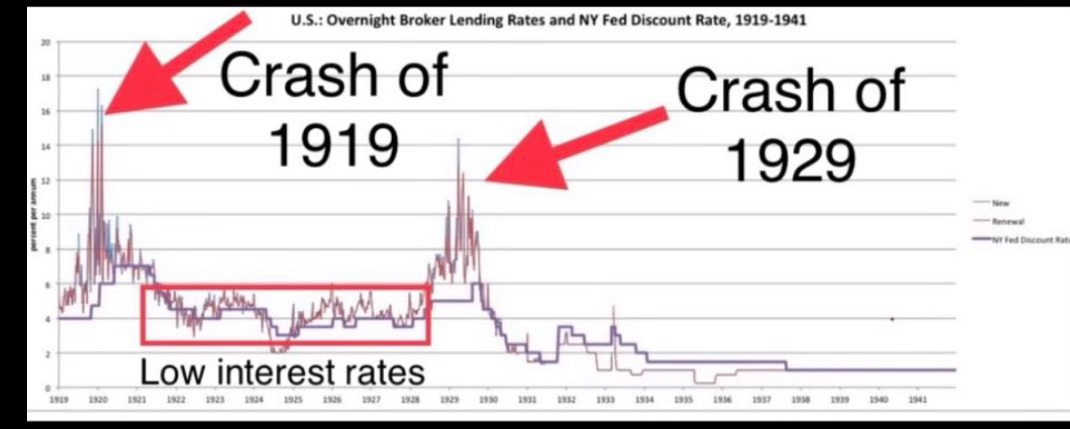

Prior to the cataclysmic Wall Street crash of 1929, stock prices soared to unprecedented heights, with the Dow Jones catapulting sixfold from August 1921 to September 1929, reaching a dizzying 381. Yet, beneath this seemingly euphoric ascent lurked ominous triggers that set the stage for an eventual financial maelstrom.

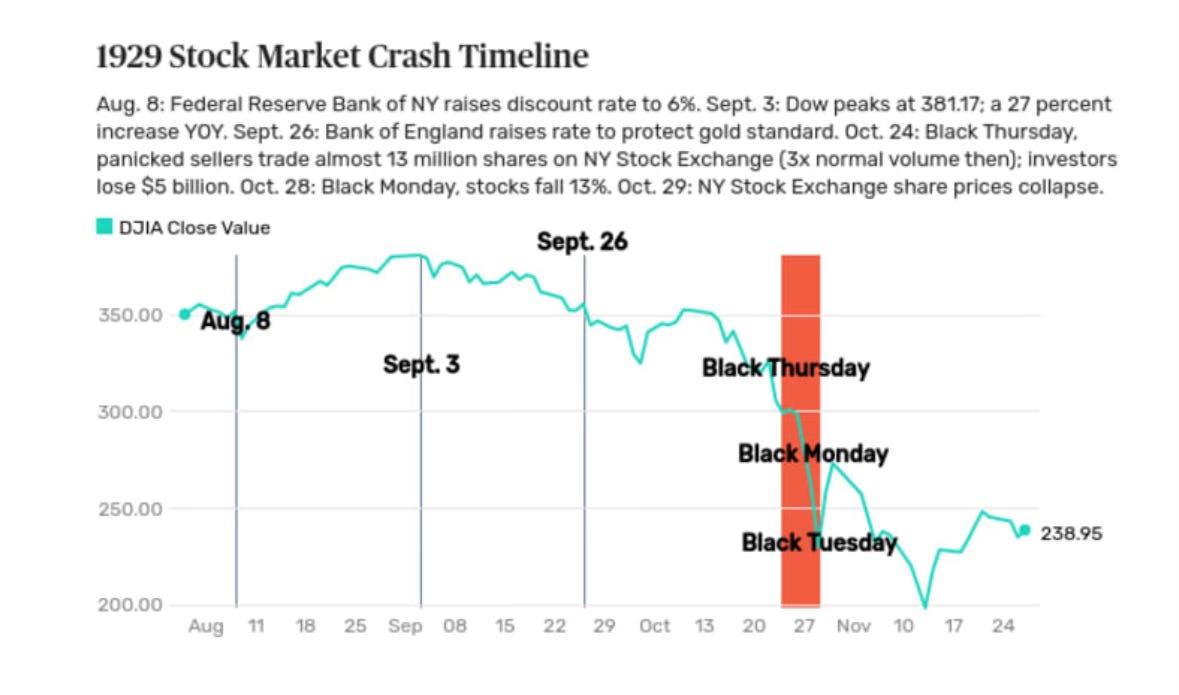

The Federal Reserve, grappling with market speculation and a surging retail frenzy, sought to curb these mounting risks by initially holding interest rates steady at 5.5% at the start of 1929, reminiscent of the climate in 2024. However, their efforts veered awry as inflationary pressures escalated, prompting a hasty rate hike to 6% in August right before the October Crash.

In August of 1929, a minor recession began, two months before the Stock Market Crash. Steel production, automobile and house sales notably declined, construction stagnated, and consumer debt reached dangerous levels due to easy credit. Margin loans for stocks exceeded $8.5 billion, surpassing the total currency in circulation in the United States at the time.

The ominous cascade began on Oct. 24, 1929, etching itself into history as Black Thursday, where the market witnessed a harrowing 21% plummet, signaling the onset of a financial unraveling. The following days saw an unfolding saga of panic-selling, with the Dow nosediving by approximately 13% on Oct. 28, compounded by another staggering drop of nearly 12% on the infamous Black Tuesday.

The repercussions echoed through the annals of economic history, culminating in the Great Depression, an era marred by a staggering 90% erosion of stock values. The harrowing aftermath of the crash cast a long shadow as the Federal Reserve failed in both parts of its mission, unable to prevent inflation and subsequent collapse of output and employment.

1987

In the tense days leading up to Black Monday in 1987, the stock market was already teetering on the edge, grappling with sky-high valuations with PE ratio of 24 and mounting concerns about economic growth, inflation, and the trade deficit as stagflation was still recent in everyone's minds. As inflation surged in September 1987, Fed Chair Alan Greenspan made a powerful decision to raise interest rates from 5.5% to 6%. The Fed's statement at the time conveyed a sense of urgency, citing the need to address potential inflationary pressures swiftly. Little did they anticipate the cataclysmic chain of events that unfolded just 30 days later. Black Monday, etched in history as the first major financial crisis of the modern global era, struck on October 19, 1987, like a thunderbolt. The Dow Jones Industrial Average hemorrhaged over $500 billion, plummeting by a staggering 22.6% in a single day—the most substantial one-day stock market decline ever recorded. The stage had been set by a series of ominous developments, from a ballooning trade deficit to a weakening dollar, eroding investor confidence and setting off a domino effect of market turmoil. Markets across Asia, from New Zealand to Mexico, were already reeling, reflecting the interconnectedness of global financial systems.

2000

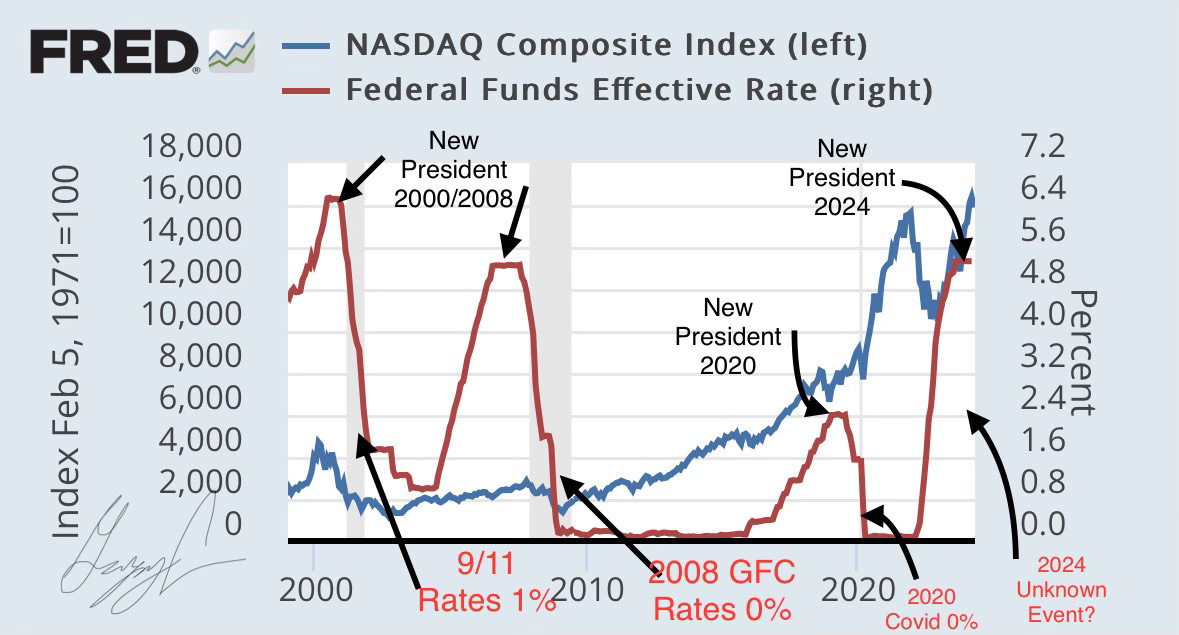

The crash of 2000 stands out as one of the most prolonged and severe downturns in recent memory, characterized by the spectacular implosion of the Nasdaq bubble. This tech frenzy took three agonizing years to deflate fully (2000-2003), witnessing a jaw-dropping 80% plunge from peak to trough. It wasn't until a staggering 16 years later that the Nasdaq index finally clawed back to its previous highs, marking a harrowing journey for investors. The genesis of this catastrophic bubble lay in the exuberant surge of investments flooding into Internet and technology stocks, fueled by an unprecedented wave of startup fervor. The dizzying heights of this euphoria peaked in March 2000, only to come crashing down by December of the same year when the Nasdaq 100 index hemorrhaged more than half of its peak value. The fallout was catastrophic, wiping out a mind-boggling $5 trillion in technology-firm market value between March and October 2002, leaving investors reeling in disbelief. The turning point, perhaps ominously presaged, was the series of interest rate hikes orchestrated by Fed Chair Alan Greenspan in 1999. The financial markets were keenly attuned to Greenspan's penchant for tightening monetary policy prematurely, reminiscent of the tumultuous period of 1987. The announcement of Greenspan's reappointment triggered a massive sell-off, with the Dow plunging over 400 points as investors braced for a relentless series of rate hikes aimed at curbing inflation. The consequences were dire: rising unemployment, faltering economic growth, and a reckoning for the high-flying tech sector that had soared too close to the sun.

2008

After the bursting of Tech Bubble 1.0, Alan Greenspan slashed interest rates to 1% in 2001. This unprecedented move ignited a speculative frenzy in America's Real Estate Market, with 30-year mortgage rates plummeting from 8.5% in 2000 to 5.5% in 2003—a record low at the time. This sharp decline in borrowing costs spurred massive speculation and malinvestment as many Americans leveraged their homes like ATM machines.

Simultaneously, Wall Street fueled the fire by churning out myriad types of mortgage-backed securities, contributing to the burgeoning bubble. However, as history often repeats, gravity eventually exerted its force. On September 29, 2008, the financial world was rocked by a seismic event as the stock market plunged by a staggering 777.68 points in intraday trading, marking the largest point drop in history at that time.

In a departure from previous crashes under Alan Greenspan's tenure, this cataclysm was orchestrated under the watch of the new Federal Reserve Chair, Ben Bernanke. Bernanke's decision to raise interest rates to 5.5% in 2007 and maintain this high threshold into 2008 triggered a chain reaction of economic turmoil, despite his earlier assertion that "Subprime is contained."

The repercussions of Bernanke's interest rate policies reverberated across the financial landscape, rendering once-valuable assets like mortgage-backed securities worthless, earning them the ominous moniker of "toxic assets." This toxic fallout unfolded in a series of harrowing events:

July 11, 2008: Subprime mortgage lender IndyMac collapses, signaling the start of a wave of mortgage defaults.

September 7, 2008: The government seizes control of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, which guaranteed millions of bad loans.

September 15, 2008: Lehman Brothers goes bankrupt under the weight of $613 billion in debt, much of it due to investments in subprime mortgages.

September 16, 2008: The government bails out insurance company AIG by acquiring 80% of it. However, Lehman Brothers does not receive a bailout, leading to the collapse of many other banks.

March 5, 2009: The Dow Jones closes at 6,926, a plunge of more than 50% from its pre-recession high, coinciding with the Federal Reserve's implementation of quantitative easing—a measure aimed at keeping interest rates low and increasing the money supply aka inflation.

The 2024 GOAT Stockmarket Bubble

(To continue reading, join us as a paid subscriber to unlock expert analysis of today’s stock market bubble and support our mission in informing and empowering investors worldwide. Gain access to exclusive content and help preserve your purchasing power.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Coastal Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.