The Inflation Fever: The Prescription is More Inflation

Why the Federal Reserve’s Rate Hikes Haven’t Cured Inflation

With the latest inflation report showing figures still above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target coming in at 2.2% on the Federal Reserve PCE index and 2.7% on core excluding food and energy, it feels like America has caught a serious inflation fever. It’s eerily reminiscent of the iconic SNL skit where Christopher Walken declares, “I got a fever, and the only prescription is more cowbell!” In the case of the U.S. economy, the Fed’s go-to prescription for inflation seems to be higher interest rates. Much like Walken’s relentless call for more cowbell, the Fed kept hammering away with rates hikes, hoping to solve the inflation crisis. But just as Walken’s cowbell didn’t cure the fever, the Fed’s policies haven’t provided the lasting relief we desperately need.

The Volcker Era: A Familiar Tune

To understand why this approach hasn’t worked, let’s revisit the inflationary crisis of the 1970s. Paul Volcker, then Fed Chair, took drastic action by raising interest rates to historic highs—rates we haven’t seen since. Volcker’s moves are often credited with “curing” inflation, but was this truly the silver bullet?

(The following data shows that The Federal Raises rates that are just inline with the inflation rate & during the late 1970s rates were lagging the actual inflation rate.)

So if interest rates don’t lower inflation, then what does?

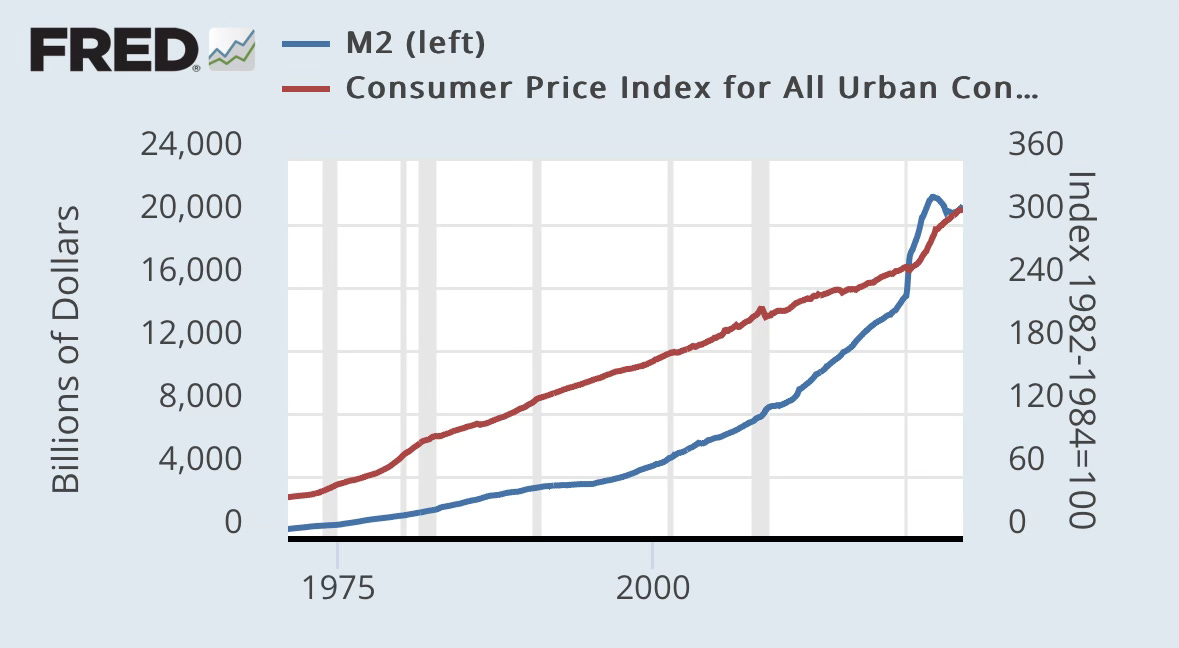

As Milton Friedman famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Inflation occurs when too much money chases too few goods, and without an increase in supply, prices rise to restore the balance.

(The following data shows the increase in money supply came first then price increases came second, then when the money supply on a Year over Year basis stoped rising or declined, lower prices follow)

The inflation of the 1970s wasn’t solved by rate hikes alone—it burned itself out as consumer spending collapsed under the weight of high prices and money supply actually declined.

Volcker himself admitted in his book Keeping at It that the Fed’s policies were insufficient at first, and it took more than high interest rates to bring inflation under control. The key issue was runaway prices, and the only thing that truly stopped inflation was when consumers could no longer afford to pay more. In essence, inflation cured itself, not because of the Fed’s “cowbell” of higher rates, but because it pushed Americans to a financial breaking point.

(The following data shows inflation, or rising prices and money supply increase since 1971. The money supply has increased 600% while total inflation has been 690% since 1971)

Economic History Repeats Itself (2024)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Coastal Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.