Top Gun Economics: Yield Curve – “Because I Was Inverted”

Feel the Need, The Need for Un-Inversion

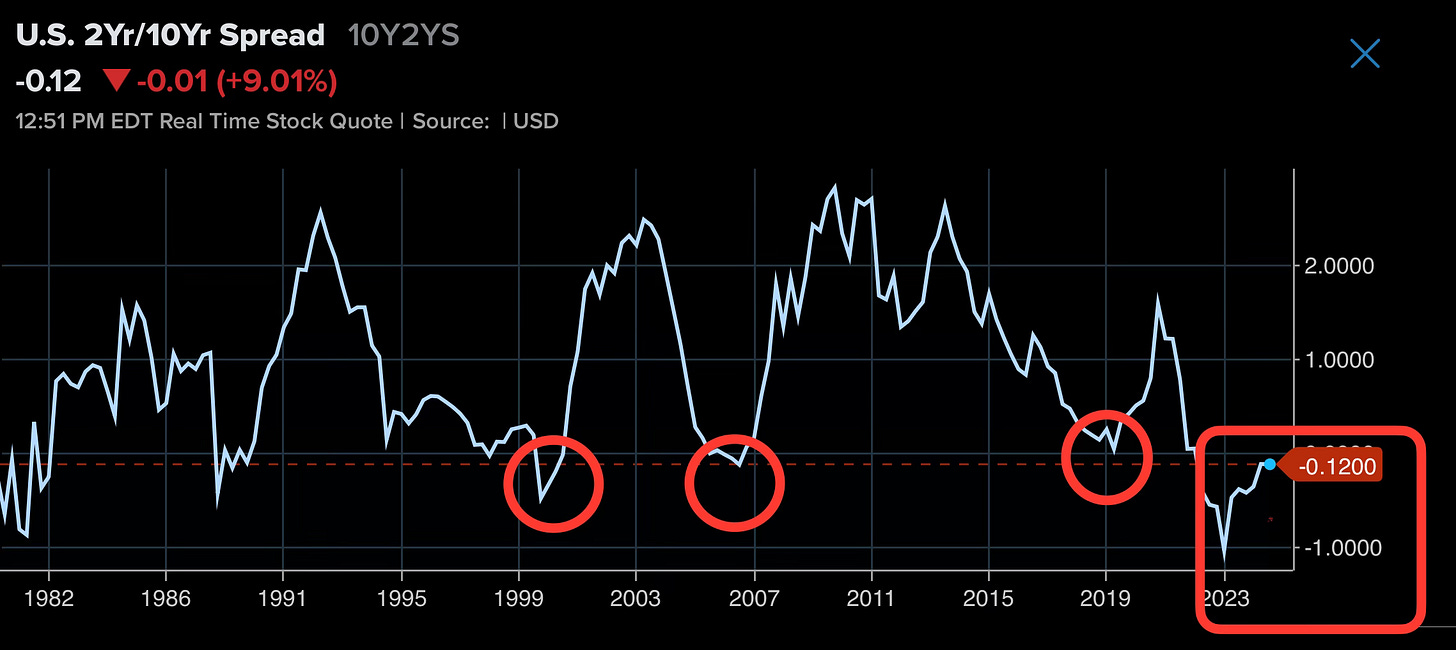

“Because I was inverted.” Maverick’s iconic line from Top Gun might sound thrilling in the cockpit, but when it comes to the U.S. bond market and the economy, it’s far from a good time. The yield curve, after enduring its longest inversion in history, is finally shifting towards un-inversion. But as any seasoned pilot—or investor—knows, the need for un-inversion isn’t necessarily a sign of safety. In fact, it might just be the prelude to even more turbulence ahead.

For months, the yield curve’s inversion—the situation where long-term bond yields fall below short-term yields—has been flashing like a warning light on a jet’s control panel, signaling potential economic danger. The inversion squeezed banks, pinching their margins as they navigated the financial turbulence, as banks were in a crisis in March 2023 (till the Federal Reserve created the Bank Term Funding Program BTFP). Now, with the curve moving towards un-inversion and banks having to pay back their BTFP loans, it’s easy to imagine that the danger zone is just starting. But as Maverick might say, just because you’ve leveled out doesn’t mean you’re out of the danger zone.

Feel the Need, the Need for Un-Inversion

When the yield curve un-inverts, it often signals that long-term rates are rising faster than short-term rates or short term rates are declining faster than the long end bonds as investors seek to buy as much short term rates as the economy slows and the Federal Reserve lowers interest rates. But here’s the catch: this shift doesn’t necessarily spell relief for banks. Instead, it can exacerbate the financial pressure they’re already under.

1. Narrowing Interest Rate Margins: Banks have been stuck in a tricky maneuver—during the inversion, they were squeezed by high short-term rates, which slashed their profit margins. Now, with the curve un-inverting, long-term rates may rise, but if short-term rates remain stubbornly high, banks could still be left with tight margins that throttle profitability. It’s like pulling out of a nosedive only to realize you’re still too close to the ground.

2. The Delayed Impact of Past Decisions: Many banks locked in long-term loans at rates during the inversion. As long-term rates climb, those loans, which looked like safe bets before, now offer lower returns. Meanwhile, the cost of borrowing could increase, putting even more pressure on profit margins—like Maverick pushing his F-14 to the limits, only to realize the engines are overheating.

3. Economic Slowdown: Un-inversion isn’t a sign of clear skies ahead. It often signals a shift from short-term turbulence to long-term challenges. The economy could be bracing for a slowdown, with reduced loan demand and higher defaults looming on the horizon. For banks, this means the ride is far from over.

4. Market Uncertainty: The process of un-inversion can stir up market volatility, making it difficult for banks to navigate the changing landscape. In the world of finance, uncertainty is the enemy of stability. Banks thrive on predictability, but an un-inverting yield curve is like flying through a storm without instruments—dangerous and unpredictable.

5. Asset-Liability Mismatch: Banks holding onto short-term assets and liabilities during the inversion might find themselves caught off guard by the sudden un-inversion. The cost of borrowing could rise faster than returns on assets, putting banks in a perilous position, much like Maverick and Goose finding themselves in a flat spin.

Banking in the Danger Zone

Take a look at the recent performance of some regional banks, and it’s clear that this un-inversion isn’t the smooth landing we’d hoped for.

Banc of California ($BANC), for instance, reported Q2 earnings of $0.10 per share, a staggering 47.37% drop from the previous year. The stock is down 9% pre-market, reflecting the deepening concerns over the bank’s financial health.

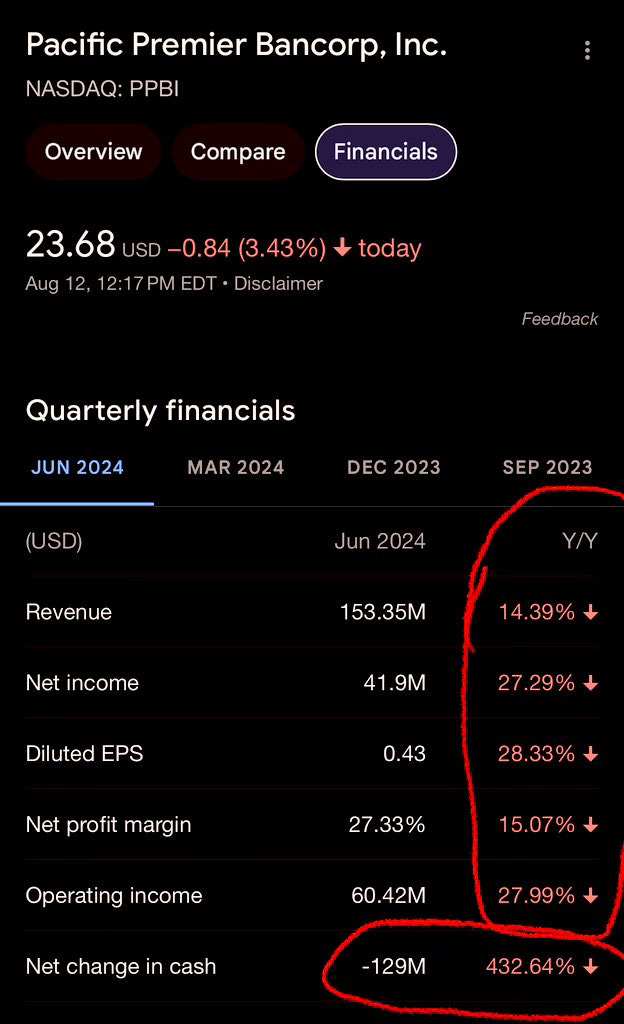

Pacific Premier Bancorp ($PPBI) isn’t faring much better, with a 15% year-over-year decline in revenue and a jaw-dropping 432% decrease in net cash. This massive cash outflow could severely impact the bank’s ability to meet obligations, raising alarms that the regional banking crisis is not just persisting—it’s getting worse.

Summit State Bank’s Q2 net income plummeted by 67% from last year, sending its stock down 15%. The sharp earnings decline underscores the broader struggles facing regional banks as they navigate the turbulent waters of an un-inverting yield curve.

Even the big players aren’t immune. Wells Fargo ($WFC) is under investigation over anti-money laundering practices and a separate SEC probe into cash sweep options for investment clients. The stock took a 7% hit as banking fears spread like wildfire.

Iceman is out: “I Feel the Need… the Need for Un-Inversion”

The transition from an inverted yield curve to a steepening one has historically been a precursor to significant market downturns. Looking back at the past 24 years worth of data when the curve inverted in 2000, 2008, and 2020, the pattern is stark and troubling.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Coastal Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.