In a twist that confounds traditional expectations, today’s stronger-than-anticipated jobs report sent shockwaves through financial markets, not necessary in a good way. The U.S. economy added 275,000 jobs in December, far outpacing forecasts, while unemployment held steady at 4.1% (U3).

Yet instead of a rally for a majority of risk assets, stocks tumbled, and interest rates rose. The S&P 500 dropped -1.4%, the Nasdaq slid -1.7%, and the 10-year bond yield increased to 4.75% & 5% on the 20 and 30 Year bond, their highest level in months. This paradoxical reaction reveals a stark truth about our financial system: what appears to be “good” for the economy isn’t always good for markets.

It’s a dynamic eerily reminiscent of Tina Turner’s timeless anthem “What’s Love Got to Do with It.” Just as Turner’s lyrics challenge the idealization of love—calling it a “second-hand emotion”—today’s markets challenge the assumption that a strong economy (based on jobs alone) automatically leads to higher stock prices.

“Who Needs a Heart When a Heart Can Be Broken?”

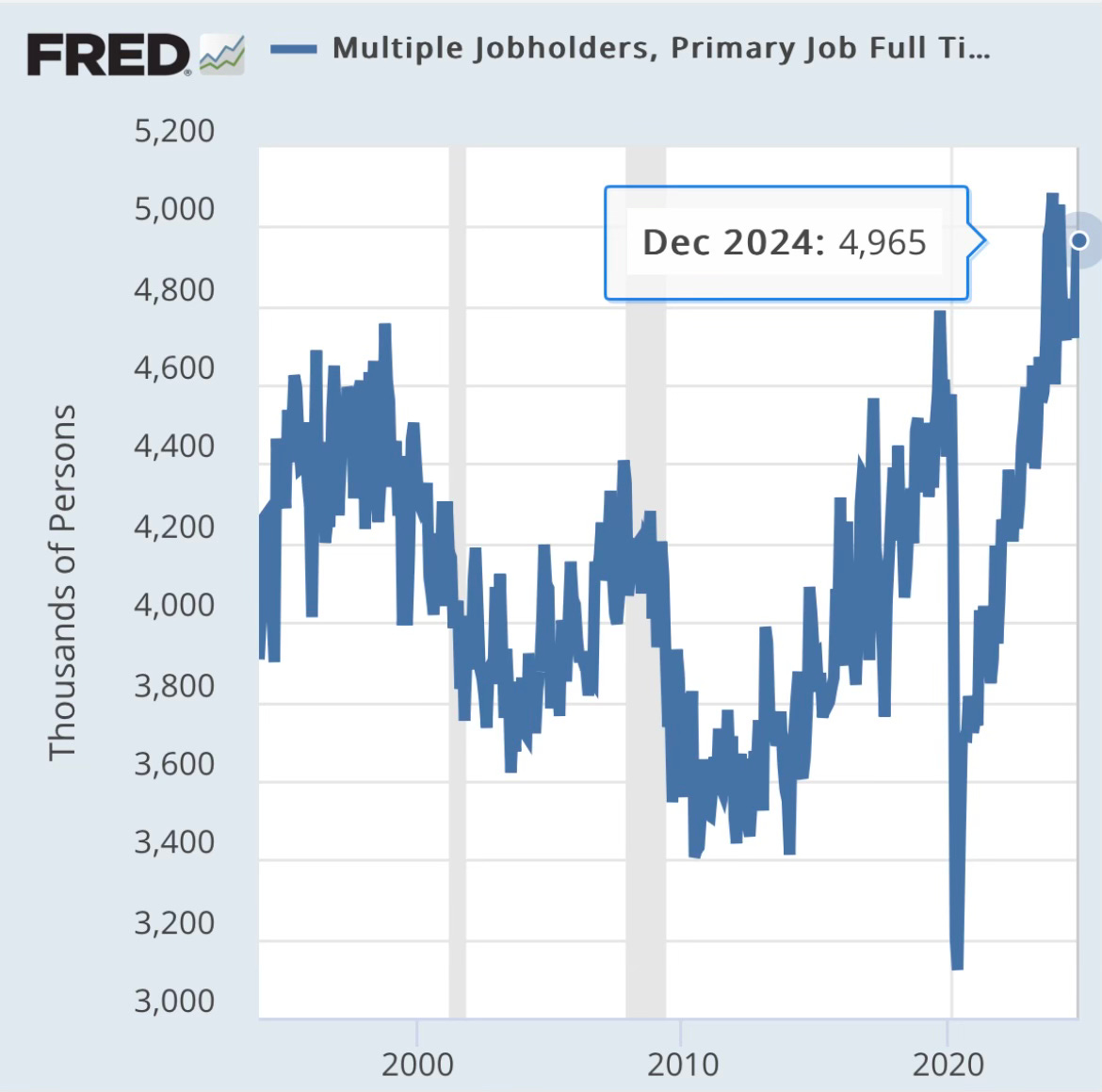

At first glance, a solid labor market should be a cause for optimism. Usually, job growth fuels consumer spending, which drives corporate profits. But in the current environment, where inflation remains a lingering concern as we enter year five of the inflation crisis, better economic data can be a double-edged sword. The headline jobs data is also misleading—near-record numbers of Americans are working two jobs, whether a combination of full-time and part-time jobs or even two full-time jobs.

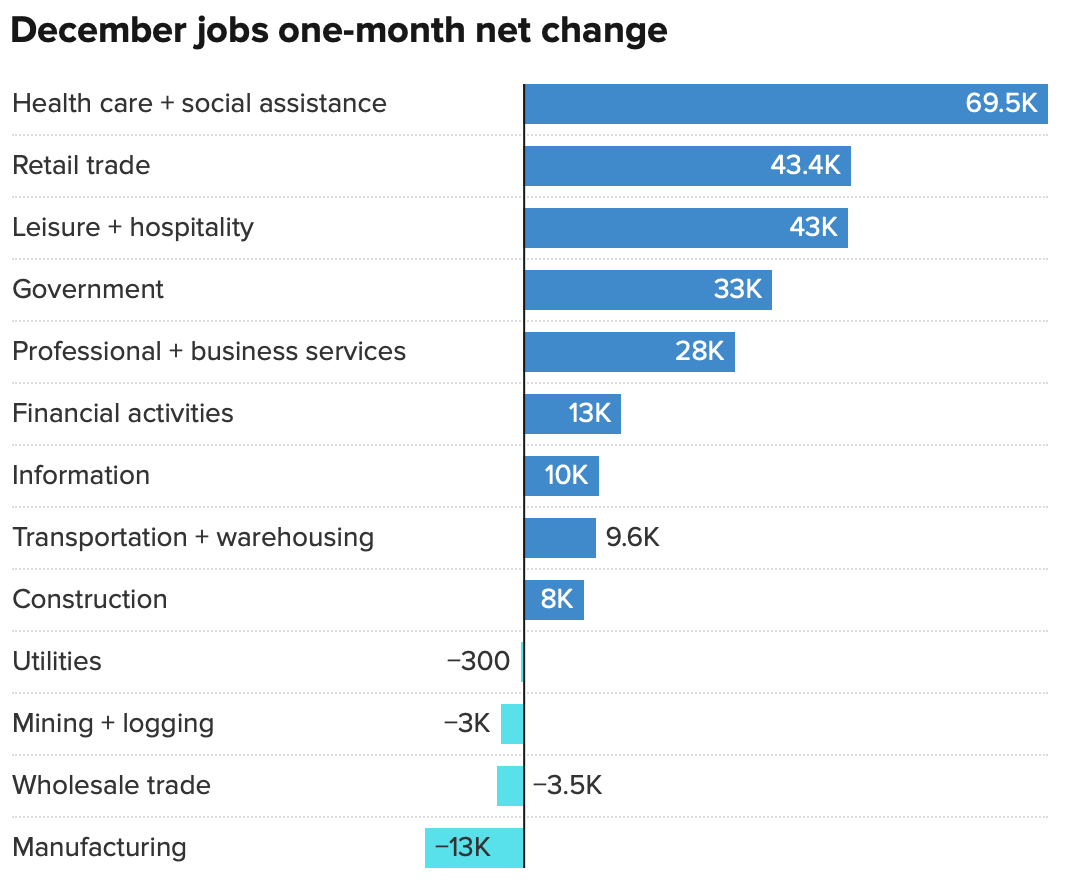

This trend lays bare the brutal reality of inflation’s grip on American households, where the erosion of purchasing power has pushed countless individuals into the grueling necessity of juggling two jobs just to keep their heads above water. Beneath the veneer of a “strong” labor market lies a far grimmer truth—a nation straining under the weight of economic hardship. The façade of resilience crumbles further when you consider that the majority of new jobs added (86,000) to the economy were concentrated in Retail Trade, such as department stores (ie Target), and Leisure and Hospitality (restaurants including bartenders and waitstaff). (These jobs are considered side hustles & not a main source of income)

Meanwhile, the jobs America truly needs—like those in Manufacturing, Utilities, and Wholesale Trade—saw net losses, signaling a worrying contraction in sectors critical to long-term economic stability. Even more startling is the lackluster performance in IT jobs, which, in an era of the AI boom, should be surging. Instead, IT managed to add only a meager 10,000 jobs, far from the robust growth expected during such transformative times. These troubling data points expose the underlying fragility of the labor market and cast doubt on the sustainability of its so-called strength

For investors, hotter economic growth signals that the Federal Reserve pays attention to maintain or even increase interest rates to prevent what they call is an “overheating” economy. The rise in rates which comes with hotter economic data hurts stocks in two ways:

1. Borrowing Costs Increase: Higher rates make it more expensive for businesses and consumers to borrow, reducing demand and slowing growth.

2. Valuations Decline: As rates rise, the future cash flows of companies—particularly growth stocks—are discounted more steeply, leading to lower stock prices.

Much like Turner’s rhetorical question, “Who needs a heart when a heart can be broken?” the financial markets seems to ask: “Who needs growth when growth can hurt risk assets?”

The Financial System: Opposite of What It Seems

The counterintuitive nature of today’s market reaction underscores a broader truth: our financial markets often works in ways that defy conventional logic.

• Good News Can Be Bad News: Good economic data prompts the Fed to tighten monetary policy, which can weigh on stocks and bonds. Conversely, weak economic data can spark rallies if investors believe it will lead to lower rates.

• Risk Assets Are Fragile: Stocks, seen as a barometer of economic health, are highly sensitive to policy shifts. What benefits the broader economy—higher wages, stable employment—can destabilize markets by compressing corporate margins or tightening financial conditions.

• Wealth Concentration: Despite the ideal of markets creating shared prosperity, gains often disproportionately benefit the wealthy. Stronger economic data can exacerbate inequality when rate hikes weigh on middle-class borrowers.

In Turner’s words, “What’s love but a sweet old-fashioned notion?” In much the same way, the notion that markets reward economic strength feels increasingly outdated in today’s environment.

The question is, Why does this happen?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Coastal Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.